The WWF is run at a local level by the following offices...

- WWF Global

- Adria

- Argentina

- Armenia

- AsiaPacific

- Australia

- Austria

- Azerbaijan

- Belgium

- Bhutan

- Bolivia

- Borneo

- Brazil

- Bulgaria

- Cambodia

- Cameroon

- Canada

- Caucasus

- Central African Republic

- Central America

- Central Asia

- Chile

- China

- Colombia

- Croatia

- Democratic Republic of the Congo

- Denmark

- Ecuador

- European Policy Office

- Finland

Mobile phones, solar panels and electric vehicles are made from a variety of transition minerals. The likes of lithium, cobalt, graphite, chromium and zinc. With these unseen transition minerals embedded in our modern lives, why don’t we know more about them, where they come from or how they are mined?

The need for transition minerals really hit home when I heard about the rapid growth in demand!

A World Bank estimate is that there will be a 500% increase in demand for minerals such as graphite, lithium and cobalt by 2050 to meet the needs of the global just transition to a new energy order.

While working on various communications products at WWF, I’ve learnt about a range of energy topics from solar to wind turbine value chains, and recently, responsible mining of transition minerals in Africa.

I’ve read that cobalt is the most expensive raw material used to build the lithium-ion batteries in smartphones and solar panels are made using multiple transition minerals, from aluminium to zinc.

Mining is always a hot topic of discussion. If you find yourself in a conversation about the mining of “transition minerals”, here are six FAQs to understand more about them and why the responsible mining of these minerals is necessary in Africa.

The defining quality of transition minerals is that they are essential for the transition to low-carbon technologies. Transition minerals are essential inputs into many clean energy technologies and associated infrastructures, such as wind turbines, solar panels and electric vehicles. These low-carbon technologies are crucial in transitioning away from carbon-emitting fossil fuels.

Transition minerals are also sometimes referred to as green minerals or a sub-category of critical minerals. Examples include copper, cobalt, nickel, lithium, graphite, rare earth elements, platinum-group metals, fluorspar, chromium, zinc, tungsten and aluminium.

Most transition mineral ores are found in the Global South, in particular in Africa, as well as China and Australia. South Africa dominates with platinum-group metals mining and reserves. The Democratic Republic of Congo has significant cobalt mining and reserves, and a large share of copper. Morocco has phosphate, Mozambique has titanium and graphite, Gabon has manganese, and Guinea has bauxite, a sedimentary rock that is the world’s main source of aluminium.

Transition minerals are in high demand. The demand mostly comes from the Global North and China. Yet most are mined in the Global South.

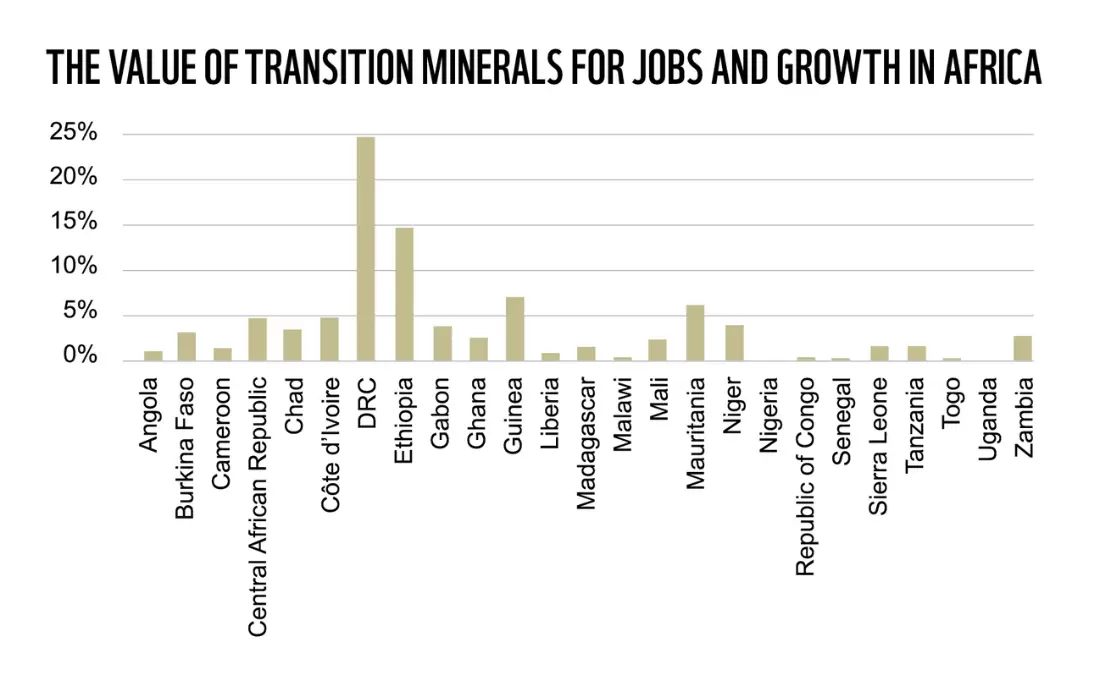

For many African countries, mining is a big source of jobs and economic growth.

Extraction of transition minerals should not only serve the interests of the Global North. The mining of transition minerals must benefit Africa, while minimising or avoiding negative impacts on water, land and biodiversity.

Source: Graphs constructed using data from EITI reports, using the latest year provided for each country on the website as at April 2025. South Africa is not a member of the EITI, which thus does not publish data for the country.

WWF’s transition minerals discussion paper explores how sustainability ambitions will be challenged by the mining of transition minerals, bringing increased risks for human rights abuses, food insecurity and water disputes. It says around 60% of transition mineral projects globally are in food-insecure places, 53% of projects are in high water risk locations and 43% of projects are in jurisdictions where there are risks to resource governance.

Before decisions to pursue mining are considered, countries would do well to have a national framework for land use. There should be tools in place to consider the options and trade-offs of different land uses, from freshwater resources to food production, carbon sinks to biodiversity and ecosystems.

A more sustainable alternative to virgin mining is to create circular economies around transition minerals. This will create new industries and jobs.

I was comforted to see examples where South Africa is already showing movement in this direction. From the trading of scrap metals like copper, aluminium, steel and lead to innovations in reclaiming transition minerals from polluted water bodies and tailings dams (areas of fine-grain mining waste).

Sustainable development in the transition minerals industry is pertinent as South Africa prepares to host the G20 nations in November 2025, where many of the players in the new world order will be present.

2025 marks the first G20 Summit to be hosted on African soil. The focus will be on Africa. And mining in Africa is a hot topic.

We need country leaders and business champions to drive and implement the best decisions for all of Africa’s citizens. We should all want to see responsible mining that doesn’t devastate communities, landscapes and oceans. It’s about ensuring the right checks and balances are in place early on to keep the world and our shared climate within safe-operating limits in 25 years’ time.

From now until 2050 is a small but serious “moment” of action. Either we act responsibly or we don’t.

2050 is only 25 years away.

If I think back 25 years, to the year 2000, everyone was worried about the “Y2K bug”. It was the great digital switchover from analogue. Back then, mobile phones were in their infancy. I got my first one in 1999, a Nokia 5110. I didn’t even consider what it was made of!

As game-changing tech inventions go, the Apple iPhone was released in 2007 and Tesla’s first completely electric Roadster launched in 2008. Both of these require many minerals in their many components. And the demand has grown exponentially since.

Who knows what tech will emerge from now until 2050 – and what new transition minerals it will require. Let’s hope the decision-makers in the G20’s hot seats will make choices that benefit people and planet.

Find out about transition minerals and what our country leaders need to do ensure responsible mining